Update on Cluster Headaches: From Genetic to Novel Therapeutic Approaches

Article information

Abstract

Cluster headaches affect 0.1% of the population and are four times more common in males than in females. Patients with this condition present with severe unilateral head pain localized in the frontotemporal lobe, accompanied by ipsilateral lacrimation, conjunctival injection, nasal congestion, diaphoresis, miosis, and eyelid edema. Recently, the first genome-wide association study of cluster headaches was conducted with the goal of aggregating data for meta-analyses, identifying genetic risk variants, and gaining biological insights. Although little is known about the pathophysiology of cluster headaches, the trigeminovascular and trigeminal autonomic reflexes and hypothalamic pathways are involved. Among anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibodies, galcanezumab has been reported to be effective in preventing episodic cluster headaches.

INTRODUCTION

Cluster headache (CH) is a trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia (TACs) that constitutes a primary headache disorder. Harris (1869–1960) confined the characteristics of CH in his article.1 He marked a distinct entity of CH, separating it from migraine and documenting its unilateral nature, severity, associated autonomic characteristics, and attack frequencies. This is the comprehensive review on CH in the English medical literature and aligns with the International Classification of Headache Disorder-3 (ICHD-3).2

CH is an excruciating primary headache disorder that affects approximately 0.1% of the general population. It manifests itself as severe unilateral pain in the trigeminal nerve distribution, ipsilateral cranial autonomic features, and agitation during attacks.

There are several effective acute treatments, which benefit slightly more than 50% of patients with CH. Historically, it has been difficult to manage CH using preventive drugs introduced for non-headaches. However, advanced understanding based on genetic and neuroimaging studies has revealed key neuropeptides and brain structures that can serve as therapeutic targets for CH.

This review covers a comprehensive view of CH, including its cardinal clinical features, epidemiology, and recent pathophysiological understanding derived from neuroimaging studies. Established treatments are discussed, along with the outcomes of studies on emerging treatments.

CLINICAL FEATURE

The patient had severe unilateral cephalalgia localized to the frontotemporal region, accompanied by autonomic nervous system manifestations, including ipsilateral lacrimation, conjunctival injection, nasal congestion, diaphoresis of the forehead and face, miosis, ptosis, or eyelid edema.3,4 These headache episodes last for varying durations, ranging from minutes to hours, with recurrent patterns that last for several days, constituting the clinical presentation of CH. This nomenclature is derived from its distinctive cyclic recurrence characterized by alternating periods of relative quiescence and clustered episodes of heightened pain intensity. This condition encompasses episodic and chronic phenotypes aligned with the taxonomy stipulated in ICHD-3.2

Without therapeutic intervention, CH attacks can be transient and last anywhere between 15 minutes and 3 hours, with an average of 45–90 minutes. During these episodes, patients present with ipsilateral cranial autonomic symptoms, including lacrimation, eye erythema, ocular discomfort, ptosis, aural fullness, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, flushing, and throat swelling. These cranial autonomic symptoms occur simultaneously with pain and are caused by parasympathetic activation. Sympathetic dysfunction can manifest itself as miosis or partial Horner syndrome.5,6

A notable feature of CH attacks is restlessness and agitation, which distinguish them from migraines. Patients with migraine or migraine patients prefer immobility during an episode, meanwhile patients with CH engage in pacing or rocking motions, applying pressure to the affected area to mitigate pain intensity. Typically, post-attack patients remain pain-free until the onset of subsequent episodes.4,7 In particular, there is a nocturnal predilection for attacks, with patients reporting an association with sleep disturbances. Interestingly, the attacks showed a consistent circadian pattern that occurred within a specific daily timeframe.

The temporal extent of recurrent attacks of CH is referred as a "bout" and is on average between 6 and 12 weeks in duration.2 Patients with CH may experience bouts interspersed with periods of remission that span months or years.4

Episodic and chronic CH can be classified according to the duration of remission between bouts. Discrimination between episodic and chronic presentations can help guide therapeutic decisions. Patients with episodic CH may discern seasonal patterns during their bouts.

Patients with chronic CH8 may have headaches that last more than a year without remission or may experience less than 3 months of remission.4 Some patients with chronic CH may experience increased attacks during these seasonal transitions.9

EPIDEMIOLOGY

CH, the predominant entity within TACs, exhibits a relatively low incidence when juxtaposed with primary headaches, such as tension-type headaches or migraine, demonstrating an estimated prevalence of 0.1%.10 Meta-analytical findings indicated a lifetime prevalence of 124 per 100,000 for CH.11 Given that approximately 10% of people affected by CH transition to chronic form11 the expected prevalence of chronic CH ranges from 10 to 15 individuals per 100,000 individuals.

1. Sex and age

CH occurs four times more frequently in males than in females. Although there was a male predominance of CH, there were no significant differences in prevalence rates between episodic and chronic CH. A sub-analysis of the sex ratio by age of onset showed that the male-to-female ratio was highest at the age of onset of 20–49 years, with 7.2:1 in episodic and 11:1 in chronic CH. The male-to-female incidence ratio was lowest in those aged >50 years, 2.3:1 in episodic CH, and 0.6:1 in chronic CH.12 The study found that circadian rhythmicity of CH attacks was more common in female (73.6%) than male (63.3%). Female group also had a higher frequency of nocturnal attacks.13

2. Trigger factor

The authors suggested that the decrease in the male-to-female ratio could reflect changes in female lifestyles over several decades, potentially due to increased smoking and alcohol consumption.11 Among the individuals who reported triggers, alcohol emerged as the most prevalent provoking factor for CH attacks, with a higher reporting rate among male participants than among their female counterparts, consistent with previous findings.

One hypothesis is that males with episodic CH may have higher alcohol consumption patterns than females with episodic CH and that this imbalance may persist during active bouts compared to female participants.13

Other frequently cited factors included stress and lack of sleep, which were reported more frequently in female than male participants.14,15 Previous research has shown that female participants are more susceptible to stress-induced hyperarousal, which is characterized by heightened agitation, restlessness, and sleep disturbances. This highlights sex-specific distinctions in stress response mechanisms.

However, male participants may experience stress-induced cognitive deficits and subsequent structural and functional changes in the regions of the brain.13 Sleep deprivation due to stress-induced arousal can trigger CH attacks in female patients. The causal relationship between attack triggers and headache still requires further elucidation.

3. Genetics

The first genome-wide association study of CHs to aggregate data for meta-analysis, identify genetic risk variants, and gain biological insights was reported in 2023.8 This study was carried out in a total of 4,777 clinically diagnosed CH cases in 10 cohorts in Europe and one cohort in East Asia. The heritability estimate for CH was 14.5%, and the meta-analysis identified nine independent signals at seven loci (DUSP10, MERTK, FTCDNL1, FHL5, WNT2, PLCE1, and LRP1) of genome-wide significance, and one additional locus (CAPN2) in the trans-ethnic meta-analysis. Three of the identified loci (FHL5, PLCE1, and LRP1) were also associated with migraine. Furthermore, a causal effect of smoking intensity on CH was shown.

CHs are associated with the chronobiological system. Two (MERTK and FHL5) of the four loci identified in recently published genomic association studies include genes involved in circadian rhythms.16

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

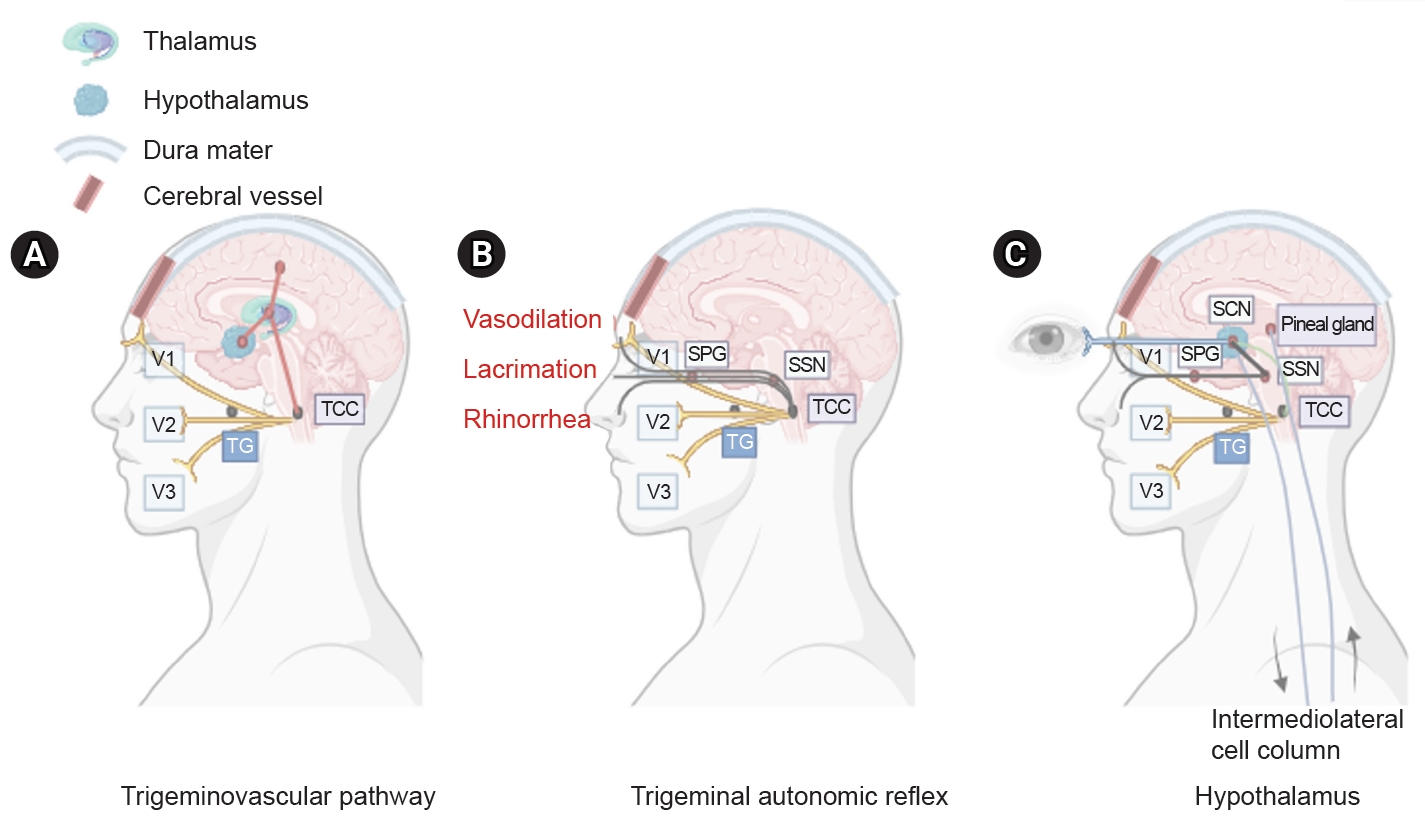

Although little is known about the pathophysiology of CH, trigeminovascular and trigeminal autonomic reflexes and hypothalamic pathways are involved (Figure 1). First, the trigeminovascular pathway plays a central role in the trigeminal distribution of severe unilateral pain. Second, cranial autonomic symptoms appear due to the trigeminal autonomic reflex. Finally, the hypothalamus may influence attack generation by contributing to circadian and circannual attack patterns.17

Three main components of cluster headache pathophysiology. (A) The trigeminal ganglion (TG) innervates the cerebral vessels and dura mater through its trigeminal branches (V1, V2, and V3) and forms synapses in the center of the trigeminocervical complex (TCC). Projections of cervical nerves from the TCC to the thalamus activate cortical structures involved in pain processing, such as the prefrontal cortex, subcortex, and cingulate cortex. (B) Trigeminal nerve terminals activate secondary TCC neurons that project to the superior salivary nucleus (SSN) of the pons and from SSN synapses to the peripheral sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG). The postganglionic parasympathetic nerves then innervate the lacrimal, nasal, and pharyngeal glands, causing autonomic symptoms. (C) The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus receives light impulse input from the retina via the retinohypothalamus, and these light impulses are transmitted to the paraventricular nucleus and then to the medial and lateral nuclei of the spinal cord, supporting postganglionic sympathetic axons. The hypothalamic region projects directly to the SSN, which in turn projects to the SPG, and nerves project to the lacrimal, nasal, and pharyngeal glands.

The trigeminovascular pathway contains neurons with cell bodies in the trigeminal ganglion, which innervate the cerebral vasculature and adjacent dura. Bipolar trigeminal ganglion neurons synapse with the trigeminocervical complex (TCC), which consists of the trigeminal nucleus caudalis of the caudal brainstem and the dorsal horn of the cervical spinal nerves C1 and C2.18 Activated trigeminovascular pathways project from the TCC to the thalamus, resulting in the activation of cortical structures involved in pain processing, including the prefrontal cortex, subcortex, and cingulate cortex.19 This results in the release of neuropeptides, including calcitonin gene-related peptides (CGRP), substance P, and neurokinin A.20

The trigeminal autonomic reflex pathway begins with the stimulation of trigeminal nerve endings, which activate secondary TCC neurons that project to the parasympathetic efferent pathway.21,22 Parasympathetic fibers originate in the superior salivary nucleus of the pons and pass through synapses in the facial (VIIth) cranial nerve and sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG). The postganglionic parasympathetic neurons of the SPG, which express pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide 38 (PACAP-38), nitric oxide synthase, vasoactive enteric polypeptide, and CGRP, innervate the lacrimal, nasal, and pharyngeal glands.

Finally, the hypothalamus plays an important role in regulating circadian rhythms, neuroendocrine homeostasis, the autonomic nervous system, and trigeminovascular nociceptive processing.23 The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus serves as the primary circadian pacemaker,24 and disruption of the mechanism underlying circadian regulation may contribute to the development of CH. Light input through the retinohypothalamic tract, which mediates the light-dark cycle using PACAP-38 and glutamate, increases the firing rate of neurons within the SCN core and regulates melatonin production. Low melatonin levels suggest SCN involvement in patients with CH.25,26

1. Neuropeptides

1) Calcitonin gene-related peptide

CGRP is an effective vasodilator that modulates nerve function. In the trigeminovascular system, CGRP is primarily localized in the sensory trigeminal ganglion. Aδ and C fibers extend to the cerebral and dural vessels, the TCC, and the spinal trigeminal tract.27,28 Binding occurs at the CGRP receptor, which consists of a calcitonin receptor-like receptor and receptor activity-modifying protein 1 (RAMP1).29-31 This receptor binds to the receptor component protein, increasing intracellular cAMP levels and subsequently activating protein kinase A (PKA), resulting in the phosphorylation of numerous downstream targets.

In individuals who experience CH, plasma levels of CGRP are elevated during attacks and return to baseline levels after treatment. Patients with chronic CH had lower levels of CGRP than those with remitted episodic CH, suggesting potential pathophysiological differences between episodic CH and chronic CH.32,33

2) Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide 38

PACAP-38 is a 38 amino acid neuropeptide found in the SPG, otic ganglion, and trigeminal ganglion and plays an important role in the trigeminovascular system and trigeminal autonomic reflex systems. The activation of the retinohypothalamic tract results in the release of PACAP-38, which mediates melatonin release.34 During spontaneous acute CH attacks, PACAP-38 levels increased. However, patients with episodic cluster, not in bouts, exhibited lower plasma levels of PACAP-38 than healthy controls. The implications of reduced inter-bout levels of PACAP-38 remain unclear, but it has been suggested that PACAP-38 is depleted during these periods, leading to decreased levels.35 These findings support the involvement of PACAP-38 in the pathophysiology of CH.

EVALUATION

A detailed history-taking and neurological examination are necessary when evaluating patients with CHs. Patients may complain of accompanying cranial autonomic symptoms such as ptosis, lacrimation, and conjunctival injection.36 Inter-bout examinations are usually normal; however, clinicians may perform brain imaging to rule out secondary causes that may mimic the CH phenotype. Magnetic resonance or computed tomography venography may be considered in cases where there is a concern for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, such as in patients with papilledema, or when Horner syndrome is suspected. However, if a patient has abnormal neurological examination results beyond the typical transient ipsilateral cranial autonomic features during an attack, further examination and evaluation may be required.

1. Evolution of the diagnostic criteria for cluster headache

The term trigeminal autonomic headache (TAC) was first coined by Goadsby and Lipton. When the first edition of the ICHD was published in 1988, the term TAC had not yet been coined, but was first introduced in the second edition of the ICHD (2004). TAC includes three types of headaches: CH, chronic and episodic paroxysmal hemicrania, and short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing.37

CH has been previously reported in several other terms, such as ciliary neuralgia, histaminic cephalalgia, Horton’s headache, Sluder’s neuralgia, sphenopalatine neuralgia, migrainous neuralgia (of Harris), and vidian neuralgia. In ICHD-1, these terms were combined into the term “cluster headache.”

In ICHD-2,38 these short-lasting headaches with autonomic features were included in rubric 3 as “cluster headaches and other trigemino-autonomic cephalalgias.” Symptoms such as restlessness or agitation were included in the diagnostic criteria. The remission period for chronic CH also changed from 14 days to 1 month.

In ICHD-3, since CH is also a trigemino-autonomic cephalalgia, the title was changed to TACs. In the 3rd edition, several additions were made to the criterion C for CH. These include forehead and facial flushing, a sensation of ear fullness, and a sense of restlessness or agitation.2 The word “chronic” for CH continues to be used in the ICHD-3. Used to mean CH with no attack-free period. Hemicrania continua and short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with cranial autonomic symptoms are newly included in TACs (Table 1).

MANAGEMENT

The approach to CH management includes immediate treatment of acute attacks and the implementation of preventive strategies to reduce or stop the recurrence of attacks during active periods. Most treatment recommendations are based on the results of open observational studies.

1. Acute management

CH attacks typically last for a short period (15–180 minutes) and peak rapidly, requiring prompt treatment. Medication overuse headaches may occur in patients with CH, especially if they have a concurrent or family history of migraine and use less effective treatments such as oral triptans, acetaminophen, or opioid receptor agonist analgesics for acute attacks.39

1) Oxygen therapy

Oxygen therapy has the advantage of having fewer side effects than triptans and is an acute treatment that can be used even during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Recommendations for oxygen inhalation include inhalation of at least 12 L/min of 100% oxygen for 15 minutes after the onset of pain, as established in randomized, double-blind trials, which showed improvement in approximately 60% of patients.40 In some cases, flow increases of up to 15 L/min for 20 minutes using a non-rebreathing mask may be necessary, and various protocols and mask types can be used.14,41 A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by the Cochrane Collaboration in 2015 included three trials of normobaric oxygen therapy compared to placebo or ergotamine tartrate involving 145 patients, and a qualitative synthesis included an additional eight trials.42 They confirmed a significant effect on attack termination and achieved a 75% response rate within 15 minutes.

2) Triptans

Subcutaneous injection of sumatriptan (6 mg) was the most effective treatment for acute cluster attacks. In an initial randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 39 patients, two cluster attacks were randomly treated with subcutaneous sumatriptan 6 mg or placebo.

The primary endpoint of this trial was defined as pain-free or almost complete relief from headache within 10–15 minutes. This was achieved in 74% of sumatriptan-treated patients and 26% of placebo-treated patients, and the success rate in reaching a pain-free state after 10 minutes was 36% for sumatriptan-treated patients and 3% for placebo-treated patients.43

Another study comparing subcutaneous sumatriptan 6 mg and 12 mg with placebo found that 35% of patients on placebo, 75% of patients on sumatriptan 6 mg, and 80% of patients on sumatriptan 12 mg had their headaches improved to mild or pain-free after 15 minutes.44

In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, sumatriptan nasal spray 20 mg showed positive results compared to placebo.45 Among the 118 patients treated for cluster attacks, the sumatriptan group had significantly better response and pain-free rates after 30 minutes than the placebo group, and no serious side effects were recorded.

In two randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials, intranasal zolmitriptan administered at doses of 5 and 10 mg was effective in alleviating pain after 30 minutes. In the first study of 92 patients, a dose of 10 mg provided 62% pain relief, compared to 40% for a dose of 5 mg and 21% for placebo. A second study of 52 patients found pain relief in 30 minutes in 63% of patients receiving 10 mg, 50% of patients receiving 5 mg, and 30% of patients receiving placebo.46

2. Transitional treatment

1) Corticosteroids

A 2021 multicenter, double-blind randomized controlled trial (RCT) found that prednisone 100 mg in the first week resulted in a rapid response with 7.1 attacks in the episodic CH group compared to 9.5 attacks in the placebo.47 A previous double-blind crossover study found that a single 30 mg dose of prednisone significantly reduced the frequency of attacks in 17 of 19 patients compared to placebo.48 In a retrospective study of 19 patients with CH, when prednisone was administered at the highest dose of 10–80 mg/day, 73% of the patients experienced more than 50% relief and 58% of the patients experienced 100% relief. However, when prednisone was tapered, typically to 10–20 mg/day, 79% of the patients experienced relapse.49 Caution is advised when using oral corticosteroids due to possible side effects, including potential complications such as osteoporosis, metabolic disease, and opportunistic infections.

Although the mechanism of action of corticosteroids in CH remains unclear, methylprednisolone has been shown to significantly reduce plasma CGRP levels and increase urinary melatonin metabolite levels in patients with CH. This suggests that corticosteroids may control cluster attacks by reducing CGRP levels; however, more studies are needed to verify this.49

It is recommended to administer prednisolone 250–500 mg intravenously in the morning or oral prednisone 60–100 mg as a single dose for 5 days, then reduce the daily dose by 10 mg every 4–5 days. If the CH recurs after reaching the dosage of 10–20 mg, it has to be increased again.50

2) Greater occipital nerve injection

Greater occipital nerve (GON) injections for CHs are effective for an average of approximately 4 weeks.51

A double-blind RCT examined three cortivazol injections over a 1-week period in 28 episodic and 15 chronic participants. The results showed that 95% of the active group and 55% of the placebo group experienced two or fewer attacks per day 2–4 days after the third injection.52 Another double-blind RCT found that 85% of 16 intermittent and seven chronic participants were seizure-free 1 week after receiving a single dose of betamethasone.51

Most clinics use 2.5 mL of betamethasone and lidocaine (0.5 mL) 2% for ipsilateral pain injections. Considering the side effect of the steroid, it is generally considered safe to administer once every 3 months, and repeated nerve blocks in medically refractory patients with chronic pain have provided temporary relief in only one-third of attacks. This type of block is generally permitted in pregnant and breastfed women. It is well tolerated, but its side effects include tenderness at the injection site, temporary worsening of headache, presyncope, and alopecia at the injection site. The exact mechanism of this effect is not well known; however, it is believed to occur through a modulatory effect on the nociceptive processing of trigeminal neurons through the trigeminovascular system.53

3. Prevention of cluster headache

Preventive measures are necessary for people experiencing episodic CH bouts lasting more than 4–8 weeks. This is particularly applicable to patients with chronic CH. Among the available treatments, verapamil is the most effective, supported by robust scientific evidence, followed by lithium (Table 2).

1) Verapamil

Verapamil is the preferred medication for headaches. In the initial randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 30 patients, patients with episodic CHs given verapamil 120 mg three times daily for 2 weeks or placebo were found to have a significantly reduced frequency of headaches.54 Two open clinical trials further evaluated the efficacy of verapamil, with 72 patients starting treatment at 200 mg. Complete relief from cluster attacks was observed in 49 of 52 patients with episodic CH and 10 of 18 patients with chronic CH.55 Typically, patients are prescribed 200 to 480 mg of verapamil, but if the dose exceeds 480 mg, arrhythmias can occur; therefore, an electrocardiogram is required.56 In clinical practice, most patients start by taking 80 mg 3 to 4 times a day and increase the dose by 80 mg every 3 to 4 days. Once the daily dose reaches 480 mg, an Electrocardiogram should be traced every 160 mg. Under regular electrocardiogram examination and supervision of a cardiologist, the dosage can finally be increased to 1,000 mg.50

2) Lithium

Lithium can be used as a secondary preventive agent. A meta-analysis of three published clinical trials involving 103 patients reported that 77% of the patients achieved complete remission or reduced attack frequency by more than 50% with lithium.57-59

Lithium has shown an efficacy similar to that of verapamil in comparative studies, but it has several side effects compared to verapamil.60 Lithium treatment requires monitoring of plasma lithium levels (range, 0.4–0.8 mEq/L) along with regular renal and thyroid function tests.

3) Topiramate

In an open study of 36 consecutive patients, including 26 with episodic CH and 10 with chronic CH, doses of 100 to 150 mg daily were shown to reduce cluster seizures by >50%.61 In a prospective Spanish study of 26 patients, including 12 with episodic CH and 14 with chronic CH, topiramate at a maximum dose of 200 mg alleviated cluster periods in 15 patients and reduced cluster attacks by more than 50% in six patients.62

4) Valproate

RCT on the effectiveness of sodium valproate for CH, 96 participants received 1,000–2,000 mg of sodium valproate or placebo daily for 2 weeks; however, there was no statistical difference between sodium valproate and placebo.63

5) Gabapentin

In a study of eight patients with episodic CH and four patients with chronic CH who did not respond to existing preventive medications, the administration of 1,000 mg of gabapentin significantly reduced the duration of CH.64

6) Melatonin

Research has been conducted on the potential effects of melatonin on the circadian rhythm of CH. A small, randomized trial of 20 patients with CH examined the effects of melatonin 10 mg or placebo administered at bedtime for 14 days in a double-blind, placebo-controlled design. Melatonin significantly reduced the number of cluster attacks, with 50% of the patients responding.65

4. New emerging treatment

1) Monoclonal antibodies against calcitonin gene-related peptide

Monoclonal antibodies against CGRP offer the potential for the first targeted therapy in CH. CGRP plasma concentrations increase in patients with spontaneous and induced CH attacks and decrease to baseline levels after sumatriptan and oxygen administration.66 Among the anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies that have recently been developed as migraine treatments and have shown good results, galcanezumab has been reported to be effective in preventing episodic CH. In a double-blind RCT, the primary endpoint was the frequency of headaches between 1 and 3 weeks after galcanezumab injection. Compared to the placebo group, the frequency of CH per week decreased more in the galcanezumab treatment group within weeks 1 to 3, and the response rate (reduction of frequency by more than 50%) in week 3 was 71% in the treatment group, which was significantly higher than 53% in the placebo group.67 However, a similar study of the anti-CGRP monoclonal antibody fremanezumab in patients with episodic CH has negative results.41 Additionally, anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies are known to have failed in clinical trials for chronic CH.68 On this basis, galcanezumab has been approved for the treatment of episodic CH in the United States and Canada, but not in Europe. Open-label trials of eptimezumab69 and erenumab70 for chronic CH are currently being conducted.

2) Neuromodulation and invasive procedures

To date, invasive and non-invasive neurostimulation techniques have been attempted as new preventive treatments for chronic CH. Non-invasive calcitonin gene-related peptide (nVNS) was administered in combination with standard treatment or standard treatment alone for 4 weeks in 92 patients with chronic CH and showed improvement in the frequency of headache attacks, 50% improvement rate, and frequency of analgesic and oxygen treatment. A significant difference was observed in the 50% response rate to attack reduction (40% in the nVNS group vs. 8% in the standard treatment group). No serious side effects have been reported.71

A case study of deep brain stimulation (DBS) targeting the hypothalamus, based on hypothalamic activation observed during CH attacks, showed encouraging results in approximately 64% of patients with refractory chronic CH.72 However, the only double-blind controlled study failed to demonstrate the superiority of DBS.73

Occipital nerve stimulation (ONS) is safer than DBS. ONS has been reported to reduce the frequency of headache attacks by approximately 60%, similar to DBS.72

3) OnabotulinumtoxinA

Multiple investigations into the effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA in managing CHs have revealed notable enhancements in headache frequency within 1 week of treatment, persisting for a duration of up to 6 months.74 A recent study underscored the high efficacy of onabotulinumtoxinA as an adjunctive therapy in individuals with refractory chronic CH.75 Additionally, a prospective study examining the treatment of intractable chronic CH through a singular injection of onabotulinumtoxinA into the SPG demonstrated a significant reduction in cluster attack frequency at the 24-week follow-up.76 In an open-label, single-center study focusing on onabotulinumtoxinA as an adjunctive therapy for the prophylactic treatment of CH, improvements were noted in some patients with chronic CH, albeit without consistent benefits observed in those with episodic CH.77

SUMMARY

The efficacy of monoclonal antibodies against CGRP has been demonstrated only in ECH. Therefore, it is necessary to develop new and effective preventive treatments for CH. Several loci have been identified in genome-wide association studies and meta-analyses of CH. CH has a circadian rhythm, and smoking has been suggested as a causal risk factor.

Notes

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

Not applicable.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: YHK; Data curation: MK, JKY, YHK; Formal analysis: MK, JKY, YHK; Investigation: MK, JKY, YHK; Methodology: YHK; Writing–original draft: MK, JKY; Writing–review and editing: MK, JKY, YHK.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research was supported by Hallym University Medical Center Research Fund (YHK).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Not applicable.