Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Headache Pain Res > Volume 25(1); 2024 > Article

-

Review Article

COVID-19 Infection-related Headache: A Narrative Review -

Yoonkyung Chang1

, Tae-Jin Song2

, Tae-Jin Song2

-

Headache and Pain Research 2024;25(1):24-33.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.62087/hpr.2024.0008

Published online: April 3, 2024

1Department of Neurology, Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea

2Department of Neurology, Ewha Womans University Seoul Hospital, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea

- Corresponding author: Tae-Jin Song, M.D., Ph.D. Department of Neurology, Ewha Womans University Seoul Hospital, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, 260 Gonghang-daero, Gangseo-gu, Seoul 07804, Republic of Korea Tel: +82-2-6986-1672, Fax: +82-2-6986-7000, E-mail: knstar@ewha.ac.kr

© 2024 The Korean Headache Society

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 8,894 Views

- 46 Download

- 5 Crossref

- Abstract

- INTRODUCTION

- CHARACTERISTICS OF AN ACUTE HEADACHE DURING COVID-19 INFECTION

- SECONDARY HEADACHES DUE TO COVID-19 INFECTION BASED ON THE INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF HEADACHE DISORDERS 3RD EDITION CLASSIFICATION

- PRIMARY HEADACHE DUE TO COVID-19 INFECTION BASED ON THE INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF HEADACHE DISORDERS 3RD EDITION CLASSIFICATION

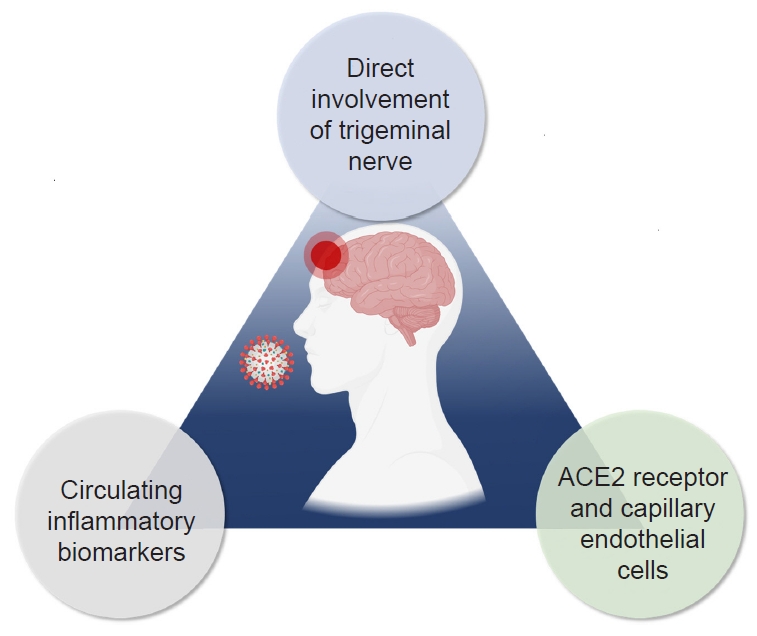

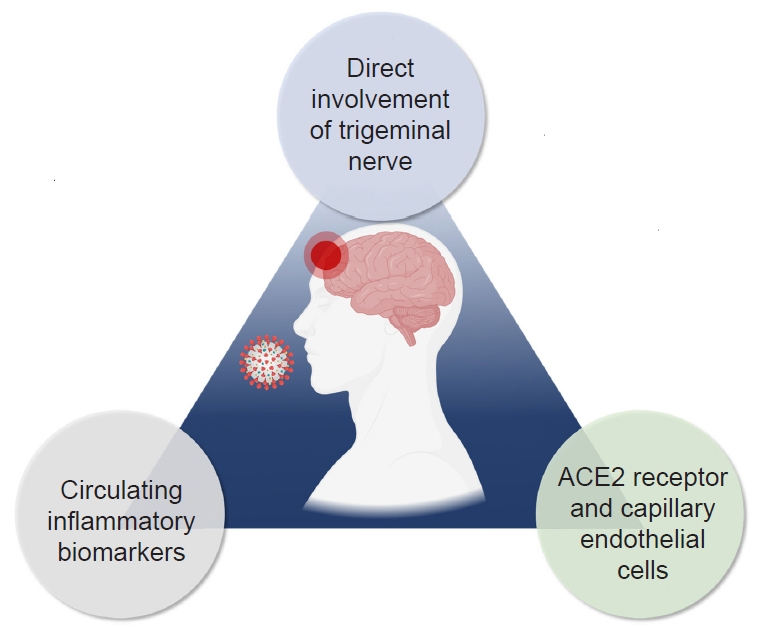

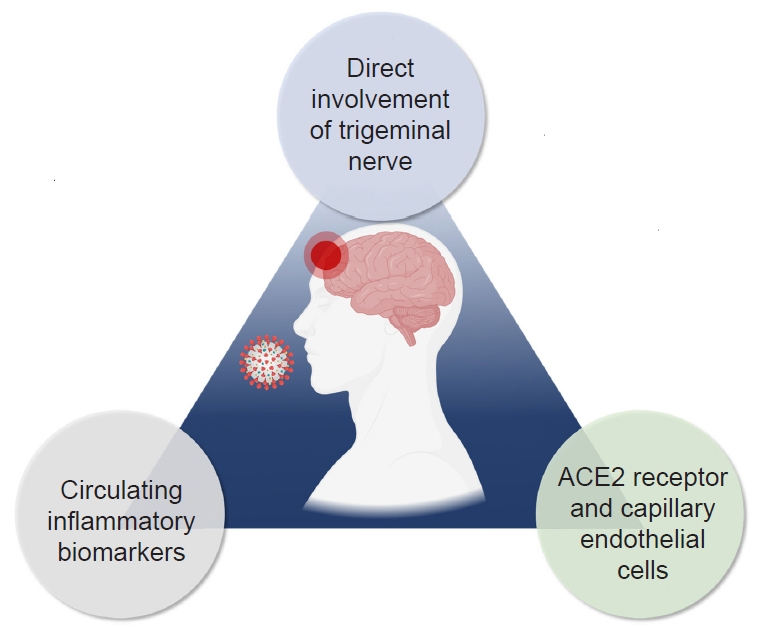

- POSSIBLE MECHANISM OF COVID-19 INFECTION-RELATED HEADACHES

- TREATMENT FOR HEADACHES RELATED TO COVID-19 INFECTION

- PERSISTENT HEADACHE AFTER COVID-19 INFECTION

- CONCLUSION

- NOTES

- REFERENCES

Abstract

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 is the virus responsible for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which caused a global pandemic and then became an endemic condition. COVID-19 infection may be associated with clinical manifestations such as respiratory symptoms and systemic diseases, including neurological disorders, notably headaches. Headaches are a common neurological symptom in individuals infected with COVID-19. Furthermore, with the transition to endemicity, COVID-19 infection-related headaches may reportedly persist in the acute phase of COVID-19 infection and in the long term after COVID-19 infection resolves. Persistent headaches after COVID-19 infection can be a significant concern for patients, potentially leading to disability. The present review discusses the clinical characteristics and potential underlying mechanisms of COVID-19 infection-related headaches.

INTRODUCTION

CHARACTERISTICS OF AN ACUTE HEADACHE DURING COVID-19 INFECTION

SECONDARY HEADACHES DUE TO COVID-19 INFECTION BASED ON THE INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF HEADACHE DISORDERS 3RD EDITION CLASSIFICATION

PRIMARY HEADACHE DUE TO COVID-19 INFECTION BASED ON THE INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF HEADACHE DISORDERS 3RD EDITION CLASSIFICATION

POSSIBLE MECHANISM OF COVID-19 INFECTION-RELATED HEADACHES

TREATMENT FOR HEADACHES RELATED TO COVID-19 INFECTION

PERSISTENT HEADACHE AFTER COVID-19 INFECTION

CONCLUSION

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: TJS; Data curation: TJS; Formal analysis: TJS; Investigation: TJS; Methodology: TJS; Software: TJS; Validation: TJS; Writing–original draft: YC, TJS; Writing–review and editing: YC, TJS.

Conflict of interest

Tae-Jin Song is the Editor of Headache and Pain Research and was not involved in the review process of this article. All authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding statement

This research was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: RS-2023-00262087 to TJS). The funding source had no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

- 1. Yoo J, Kim JH, Jeon J, Kim J, Song TJ. Risk of COVID-19 infection and of severe complications among people with epilepsy: a nationwide cohort study. Neurology 2022;98:e1886-e1892.ArticlePubMed

- 2. Chang Y, Jeon J, Song TJ, Kim J. Association between the fatty liver index and the risk of severe complications in COVID-19 patients: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2022;22:384.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 3. Chung SJ, Chang Y, Jeon J, Shin JI, Song TJ, Kim J. Association of Alzheimer’s disease with COVID-19 susceptibility and severe complications: a nationwide cohort study. J Alzheimers Dis 2022;87:701-710.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Chang Y, Jeon J, Song TJ, Kim J. Association of triglyceride-glucose index with prognosis of COVID-19: a population-based study. J Infect Public Health 2022;15:837-844.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 5. Park J, Shin JI, Kim DH, et al. Association of atrial fibrillation with infectivity and severe complications of COVID-19: a nationwide cohort study. J Med Virol 2022;94:2422-2430.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 6. Kim HJ, Park MS, Shin JI, et al. Associations of heart failure with susceptibility and severe complications of COVID-19: a nationwide cohort study. J Med Virol 2022;94:1138-1145.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 7. Chang Y, Jeon J, Song TJ, Kim J. Association of triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio with severe complications of COVID-19. Heliyon 2023;9:e17428.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 8. Pascarella G, Strumia A, Piliego C, et al. COVID-19 diagnosis and management: a comprehensive review. J Intern Med 2020;288:192-206.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 9. Ahmad I, Rathore FA. Neurological manifestations and complications of COVID-19: a literature review. J Clin Neurosci 2020;77:8-12.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 10. Mutiawati E, Syahrul S, Fahriani M, et al. Global prevalence and pathogenesis of headache in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. F1000Res 2020;9:1316.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 11. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic Manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol 2020;77:683-690.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 12. Papetti L, Alaimo Di Loro P, Tarantino S, et al. I stay at home with headache. A survey to investigate how the lockdown for COVID-19 impacted on headache in Italian children. Cephalalgia 2020;40:1459-1473.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 13. Sampaio Rocha-Filho PA, Albuquerque PM, Carvalho LCLS, Dandara Pereira Gama M, Magalhães JE. Headache, anosmia, ageusia and other neurological symptoms in COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. J Headache Pain 2022;23:2.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Trigo J, García-Azorín D, Planchuelo-Gómez Á, et al. Factors associated with the presence of headache in hospitalized COVID-19 patients and impact on prognosis: a retrospective cohort study. J Headache Pain 2020;21:94.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 15. Membrilla JA, de Lorenzo Í, Sastre M, Díaz de Terán J. Headache as a cardinal symptom of coronavirus disease 2019: a cross-sectional study. Headache 2020;60:2176-2191.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 16. García-Azorín D, Sierra Á, Trigo J, et al. Frequency and phenotype of headache in covid-19: a study of 2194 patients. Sci Rep 2021;11:14674.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 17. García-Azorín D, Trigo J, Talavera B, et al. Frequency and type of red flags in patients with Covid-19 and headache: a series of 104 hospitalized patients. Headache 2020;60:1664-1672.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 18. Caronna E, Ballvé A, Llauradó A, et al. Headache: a striking prodromal and persistent symptom, predictive of COVID-19 clinical evolution. Cephalalgia 2020;40:1410-1421.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 19. López JT, García-Azorín D, Planchuelo-Gómez Á, García-Iglesias C, Dueñas-Gutiérrez C, Guerrero ÁL. Phenotypic characterization of acute headache attributed to SARS-CoV-2: an ICHD-3 validation study on 106 hospitalized patients. Cephalalgia 2020;40:1432-1442.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 20. Hussein M, Fathy W, Eid RA, et al. Relative Frequency and risk factors of COVID-19 related headache in a sample of Egyptian population: a hospital-based study. Pain Med 2021;22:2092-2099.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 21. Vacchiano V, Riguzzi P, Volpi L, et al. Early neurological manifestations of hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Neurol Sci 2020;41:2029-2031.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 22. Rocha-Filho PAS, Magalhães JE. Headache associated with COVID-19: Frequency, characteristics and association with anosmia and ageusia. Cephalalgia 2020;40:1443-1451.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 23. Amanat M, Rezaei N, Roozbeh M, et al. Neurological manifestations as the predictors of severity and mortality in hospitalized individuals with COVID-19: a multicenter prospective clinical study. BMC Neurol 2021;21:116.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 24. Al-Hashel JY, Abokalawa F, Alenzi M, Alroughani R, Ahmed SF. Coronavirus disease-19 and headache; impact on pre-existing and characteristics of de novo: a cross-sectional study. J Headache Pain 2021;22:97.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 25. Vihta KD, Pouwels KB, Peto TEA, et al. Symptoms and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) positivity in the general population in the United Kingdom. Clin Infect Dis 2022;75:e329-e337.ArticlePubMed

- 26. Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Cuadrado ML, Gómez-Mayordomo V, et al. Headache as a COVID-19 onset symptom and post-COVID-19 symptom in hospitalized COVID-19 survivors infected with the Wuhan, Alpha, or Delta SARS-CoV-2 variants. Headache 2022;62:1148-1152.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 27. Graham MS, Sudre CH, May A, et al. Changes in symptomatology, reinfection, and transmissibility associated with the SARS-CoV-2 variant B.1.1.7: an ecological study. Lancet Public Health 2021;6:e335-e345.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 28. Brandal LT, MacDonald E, Veneti L, et al. Outbreak caused by the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in Norway, November to December 2021. Euro Surveill 2021;26:2101147.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 29. Vihta KD, Pouwels KB, Peto TE, et al. Omicron-associated changes in SARS-CoV-2 symptoms in the United Kingdom. Clin Infect Dis 2022;76:e133-e141.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 30. Kirca F, Aydoğan S, Gözalan A, et al. Comparison of clinical characteristics of wild-type SARS-CoV-2 and Omicron. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2022;68:1476-1480.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 31. Yang N, Wang C, Huang J, et al. Clinical and pulmonary CT characteristics of patients infected with the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant compared with those of patients infected with the alpha viral strain. Front Public Health 2022;10:931480.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 32. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018;38:1-211.ArticlePDF

- 33. Caronna E, Pozo-Rosich P. Headache as a symptom of COVID-19: narrative review of 1-year research. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2021;25:73.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 34. Kacprzak A, Malczewski D, Domitrz I. Headache attributed to SARS-CoV-2 infection or COVID-19 related headache-not migraine-like problem-original research. Brain Sci 2021;11:1406.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 35. Iacobucci G. Covid-19: runny nose, headache, and fatigue are commonest symptoms of omicron, early data show. BMJ 2021;375:n3103.ArticlePubMed

- 36. Saad M, Omrani AS, Baig K, et al. Clinical aspects and outcomes of 70 patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection: a single-center experience in Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis 2014;29:301-306.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 37. Tsai LK, Hsieh ST, Chang YC. Neurological manifestations in severe acute respiratory syndrome. Acta Neurol Taiwan 2005;14:113-119.PubMed

- 38. Kennedy PG. Viral encephalitis: causes, differential diagnosis, and management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75 Suppl 1:i10-i15.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 39. Porta-Etessam J, Matías-Guiu JA, González-García N, et al. Spectrum of headaches associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: study of healthcare professionals. Headache 2020;60:1697-1704.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 40. Ellul MA, Benjamin L, Singh B, et al. Neurological associations of COVID-19. Lancet Neurol 2020;19:767-783.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 41. Correia AO, Feitosa PWG, Moreira JLS, Nogueira SÁR, Fonseca RB, Nobre MEP. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19 and other coronaviruses: a systematic review. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res 2020;37:27-32.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 42. Bolay H, Karadas Ö, Oztürk B, et al. HMGB1, NLRP3, IL-6 and ACE2 levels are elevated in COVID-19 with headache: a window to the infection-related headache mechanism. J Headache Pain 2021;22:94.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 43. Trigo J, García-Azorín D, Sierra-Mencía Á, et al. Cytokine and interleukin profile in patients with headache and COVID-19: a pilot, CASE-control, study on 104 patients. J Headache Pain 2021;22:51.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 44. Al-Ani F, Chehade S, Lazo-Langner A. Thrombosis risk associated with COVID-19 infection. A scoping review. Thromb Res 2020;192:152-160.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 45. Lodigiani C, Iapichino G, Carenzo L, et al. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res 2020;191:9-14.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 46. Abboud H, Abboud FZ, Kharbouch H, Arkha Y, El Abbadi N, El Ouahabi A. COVID-19 and SARS-Cov-2 infection: pathophysiology and clinical effects on the nervous system. World Neurosurg 2020;140:49-53.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 47. García-Grimshaw M, Flores-Silva FD, Chiquete E, et al. Characteristics and predictors for silent hypoxemia in a cohort of hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Auton Neurosci 2021;235:102855.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 48. Belvis R. Headaches during COVID-19: my clinical case and review of the literature. Headache 2020;60:1422-1426.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 49. Cordenier A, De Hertogh W, De Keyser J, Versijpt J. Headache associated with cough: a review. J Headache Pain 2013;14:42.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 50. Liu X, Yang N, Tang J, et al. Downregulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 by the neuraminidase protein of influenza A (H1N1) virus. Virus Res 2014;185:64-71.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 51. Doobay MF, Talman LS, Obr TD, Tian X, Davisson RL, Lazartigues E. Differential expression of neuronal ACE2 in transgenic mice with overexpression of the brain renin-angiotensin system. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2007;292:R373-R381.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 52. Xia H, Lazartigues E. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: central regulator for cardiovascular function. Curr Hypertens Rep 2010;12:170-175.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 53. Imboden H, Patil J, Nussberger J, et al. Endogenous angiotensinergic system in neurons of rat and human trigeminal ganglia. Regul Pept 2009;154:23-31.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 54. Bolay H, Gül A, Baykan B. COVID-19 is a real headache! Headache 2020;60:1415-1421.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 55. Luers JC, Rokohl AC, Loreck N, et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Clin Infect Dis 2020;71:2262-2264.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 56. Perini F, D’Andrea G, Galloni E, et al. Plasma cytokine levels in migraineurs and controls. Headache 2005;45:926-931.ArticlePubMed

- 57. Edvinsson L, Haanes KA, Warfvinge K. Does inflammation have a role in migraine? Nat Rev Neurol 2019;15:483-490.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 58. Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet 2020;395:1033-1034.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 59. Ragab D, Salah Eldin H, Taeimah M, Khattab R, Salem R. The COVID-19 Cytokine storm; what we know so far. Front Immunol 2020;11:1446.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 60. Wagner R, Myers RR. Endoneurial injection of TNF-alpha produces neuropathic pain behaviors. Neuroreport 1996;7:2897-2901.ArticlePubMed

- 61. Yao MZ, Gu JF, Wang JH, et al. Interleukin-2 gene therapy of chronic neuropathic pain. Neuroscience 2002;112:409-416.ArticlePubMed

- 62. Herrmann F, Schulz G, Lindemann A, et al. Hematopoietic responses in patients with advanced malignancy treated with recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Clin Oncol 1989;7:159-167.ArticlePubMed

- 63. Smith RS. The cytokine theory of headache. Med Hypotheses 1992;39:168-174.ArticlePubMed

- 64. Baig AM, Khaleeq A, Ali U, Syeda H. Evidence of the COVID-19 virus targeting the CNS: tissue distribution, host-virus interaction, and proposed neurotropic mechanisms. ACS Chem Neurosci 2020;11:995-998.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 65. Planchuelo-Gómez Á, Trigo J, de Luis-García R, Guerrero ÁL, Porta-Etessam J, García-Azorín D. Deep phenotyping of headache in hospitalized COVID-19 patients via principal component analysis. Front Neurol 2020;11:583870.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 66. Magdy R, Hussein M, Ragaie C, et al. Characteristics of headache attributed to COVID-19 infection and predictors of its frequency and intensity: a cross sectional study. Cephalalgia 2020;40:1422-1431.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 67. Karadaş Ö, Öztürk B, Sonkaya AR, Taşdelen B, Özge A, Bolay H. Latent class cluster analysis identified hidden headache phenotypes in COVID-19: impact of pulmonary infiltration and IL-6. Neurol Sci 2021;42:1665-1673.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 68. Arca KN, Smith JH, Chiang CC, et al. COVID-19 and headache medicine: a narrative review of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and corticosteroid use. Headache 2020;60:1558-1568.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 69. Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Navarro-Santana M, Gómez-Mayordomo V, et al. Headache as an acute and post-COVID-19 symptom in COVID-19 survivors: a meta-analysis of the current literature. Eur J Neurol 2021;28:3820-3825.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 70. Riddle EJ, Smith JH. New daily persistent headache: a diagnostic and therapeutic odyssey. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2019;19:21.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 71. Sampaio Rocha-Filho PA, Voss L. Persistent headache and persistent anosmia associated with COVID-19. Headache 2020;60:1797-1799.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 72. Caronna E, Alpuente A, Torres-Ferrus M, Pozo-Rosich P. Toward a better understanding of persistent headache after mild COVID-19: three migraine-like yet distinct scenarios. Headache 2021;61:1277-1280.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- Unclosing Clinical Criteria and the Role of Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Persistent Post-COVID-19 Headaches: A Pilot Case-Control Study from Egypt

Ahmed Abualhasan, Shereen Fathi, Hala Gabr, Abeer Mahmoud, Diana Khedr

Clinical and Translational Neuroscience.2025; 9(1): 5. CrossRef - Exploring Secondary Headaches: Insights from Glaucoma and COVID-19 Infection

Soo-Kyoung Kim

Headache and Pain Research.2025; 26(1): 3. CrossRef - Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Monoclonal Antibody Treatment in Nine Cases of Persistent Headache Following COVID-19-Infection

Soyoun Choi, Yooha Hong, Mi-Kyoung Kang, Tae-Jin Song, Soo-Jin Cho

Journal of Korean Medical Science.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - A Prospective Multicenter Study on the Evaluation of Frequency of Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension in Korea

Byung-Su Kim, Soo-Jin Cho, Kyung-Hee Cho, Seol-Hee Baek, Jong-Hee Sohn, Tae-Jin Song, Wonwoo Lee, Hong-Kyun Park, Soohyun Cho, Junhee Han, Soolienah Rhiu, Myoung-Jin Cha, Mi Ji Lee, Min Kyung Chu

Journal of Korean Medical Science.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - Global, regional, and national burden of headache disorders, 1990–2021, with forecasts to 2050: A Global Burden of Disease study 2021

Tissa Wijeratne, Jiyeon Oh, Soeun Kim, Yesol Yim, Min Seo Kim, Jae Il Shin, Yun-Seo Oh, Raon Jung, Yun Seo Kim, Lee Smith, Hasan Aalruz, Rami Abd-Rabu, Deldar Morad Abdulah, Richard Gyan Aboagye, Meysam Abolmaali, Dariush Abtahi, Ahmed Abualhasan, Rufus A

Cell Reports Medicine.2025; 6(10): 102348. CrossRef

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link-

Cite this Article

Cite this Article

- Cite this Article

-

- Close

- Download Citation

- Close

- Figure

Figure 1.

| Possible medication | Study result | Caution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroids | There was no significant difference in the frequency or intensity of headaches that occurred after COVID-19 infection depending on whether corticosteroids were administered. | The effectiveness of corticosteroids in treating headaches after COVID-19 infection has not been proven. | 20, 66 |

| In another study, patients receiving corticosteroids were more likely to respond well to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for headaches that occurred after COVID-19 infection. | Corticosteroids can cause immune deficiency, which may be associated with opportunistic infections. | ||

| Acetaminophen, NSAIDs, metamizole, triptans, or a combination of these oral medications | Several oral medications, including combination therapy, may lead to complete or partial relief (about 25% to 54%) for COVID-19-related headaches. | The effectiveness of oral medications may be insufficient, and if accompanied by nausea and vomiting, administration can be challenging. | 15 |

| Paracetamol | About 60% of patients with headaches after COVID-19 infection showed improvement after an intravenous administration of 1 g of paracetamol. | Usually, paracetamol can be prescribed as parenteral formulations. | 67 |

| Lidocaine | Lidocaine can be used to block the greater occipital nerve, leading to relief in 85% of COVID-19-related headaches that do not respond to paracetamol. | Lidocaine can be applied for occipital nerve block. | 67 |

| NSAIDs (ibuprofen) | Concerns were raised that NSAIDs, especially ibuprofen, might be associated with worse outcomes and increased infectivity of SARS-CoV-2. However, this hypothesis was not confirmed in subsequent studies. | Care should be taken regarding renal dysfunction caused by NSAIDs. | 68 |

| Usually, NSAIDs can be prescribed as oral or parenteral formulations. | NSAID administration can mask COVID-19-related symptoms. |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Table 1.

TOP

KHS

KHS