Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Headache Pain Res > Volume 25(1); 2024 > Article

-

Review Article

Menstrual Migraine: A Review of Current Research and Clinical Challenges -

Jong-Geun Seo

-

Headache and Pain Research 2024;25(1):16-23.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.62087/hpr.2024.0004

Published online: April 22, 2024

Department of Neurology, Kyungpook National University School of Medicine, Daegu, Republic of Korea

- Correspondence: Jong-Geun Seo, M.D., Ph.D. Department of Neurology, Kyungpook National University Hospital, Kyungpook National University School of Medicine, 130 Dongdeok-ro, Jung-gu, Daegu 41944, Republic of Korea Tel : +82-53-200-5765, Fax : +82-53-422-4265, E-mail: jonggeun.seo@gmail.com

© 2024 The Korean Headache Society

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 26,243 Views

- 294 Download

- 6 Crossref

Abstract

- The term “menstrual migraine” is commonly used to describe migraines that occur in association with menstruation, as distinct from other migraine types. A significant proportion of women of reproductive age experience migraine attacks related to their menstrual cycle. Menstrual migraine is characterized by migraine attacks occurring on day 1±2 (i.e., days −2 to +3) of menstruation in at least two out of three menstrual cycles. Although the reported prevalence of menstrual migraine varies considerably, population-based studies have found that menstrual migraine affects up to 60% of women with migraines. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the etiology of menstrual migraine, among which the estrogen withdrawal hypothesis is the most widely accepted. Women who experience menstrual migraines often face considerable disability due to perimenstrual attacks. Studies have reported that perimenstrual attacks are more severe and more difficult to manage than nonmenstrual attacks. The principles of acute managing perimenstrual attacks are the same as those for managing nonmenstrual attacks. Short-term preventive therapy is needed to prevent menstrual migraines before they occur during the perimenstrual period. This review summarizes the prevalence, distinct clinical features, pathophysiological mechanisms, and management of menstrual migraine.

INTRODUCTION

PREVALENCE

CLINICAL FEATURES

DIAGNOSIS

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

MANAGEMENT

1) Standard prophylaxis

2) Short-term prevention of menstrual migraine.

CONCLUSIONS

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing: JGS.

Conflict of interest

Jong-Geun Seo is the Editor of Headache and Pain Research and was not involved in the review process of this article. Author has no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

*For the purposes of ICHD-3, menstruation is considered to be endometrial bleeding resulting either from the normal menstrual cycle or from the withdrawal of exogenous progestogens, as in the use of combined oral contraceptives or cyclical hormone replacement therapy. †The first day of menstruation is day 1 and the preceding day is day −1; there is no day 0.

| Acute treatment | Short-term prevention |

|---|---|

| NSAIDs49 | NSAIDs65 |

| Ergotamine derivatives21 | |

| Triptans | Triptans |

| Frovatriptan52 | Frovatriptan63 |

| Naratriptan45 | Naratriptan22,23 |

| Sumatriptan48 | Sumatriptan24 |

| Zolmitriptan50 | Zolmitriptan64 |

| Almotriptan44 | |

| Rizatriptan46 |

- 1. GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2018;17:954-976.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 2. Ashina M, Terwindt GM, Al-Karagholi MA, et al. Migraine: disease characterisation, biomarkers, and precision medicine. Lancet 2021;397:1496-1504.ArticlePubMed

- 3. Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Chee E, Sawyer J, Silberstein SD. Menstrual cycle and headache in a population sample of migraineurs. Neurology 2000;55:1517-1523.ArticlePubMed

- 4. MacGregor EA, Hackshaw A. Prevalence of migraine on each day of the natural menstrual cycle. Neurology 2004;63:351-353.ArticlePubMed

- 5. MacGregor EA, Frith A, Ellis J, Aspinall L, Hackshaw A. Incidence of migraine relative to menstrual cycle phases of rising and falling estrogen. Neurology 2006;67:2154-2158.ArticlePubMed

- 6. Korean Headache Society. The headache, 3rd ed. JIN & JPNC. 2022.

- 7. Verhagen IE, Spaink HA, van der Arend BW, van Casteren DS, MaassenVanDenBrink A, Terwindt GM. Validation of diagnostic ICHD-3 criteria for menstrual migraine. Cephalalgia 2022;42:1184-1193.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 8. Dzoljic E, Sipetic S, Vlajinac H, et al. Prevalence of menstrually related migraine and nonmigraine primary headache in female students of Belgrade University. Headache 2002;42:185-193.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 9. Karlı N, Baykan B, Ertaş M, et al. Impact of sex hormonal changes on tension-type headache and migraine: a cross-sectional population-based survey in 2,600 women. J Headache Pain 2012;13:557-565.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 10. Vetvik KG, Macgregor EA, Lundqvist C, Russell MB. Prevalence of menstrual migraine: a population-based study. Cephalalgia 2014;34:280-288.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 11. Mattsson P. Hormonal factors in migraine: a population-based study of women aged 40 to 74 years. Headache 2003;43:27-35.ArticlePubMed

- 12. Couturier EG, Bomhof MA, Neven AK, van Duijn NP. Menstrual migraine in a representative Dutch population sample: prevalence, disability and treatment. Cephalalgia 2003;23:302-308.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 13. Russell MB, Rasmussen BK, Fenger K, Olesen J. Migraine without aura and migraine with aura are distinct clinical entities: a study of four hundred and eighty-four male and female migraineurs from the general population. Cephalalgia 1996;16:239-245.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 14. Tepper SJ, Zatochill M, Szeto M, Sheftell F, Tepper DE, Bigal M. Development of a simple menstrual migraine screening tool for obstetric and gynecology clinics: the menstrual migraine assessment tool. Headache 2008;48:1419-1425.ArticlePubMed

- 15. Granella F, Sances G, Pucci E, Nappi RE, Ghiotto N, Napp G. Migraine with aura and reproductive life events: a case control study. Cephalalgia 2000;20:701-707.Article

- 16. Cupini LM, Matteis M, Troisi E, Calabresi P, Bernardi G, Silvestrini M. Sex-hormone-related events in migrainous females. A clinical comparative study between migraine with aura and migraine without aura. Cephalalgia 1995;15:140-144.ArticlePDF

- 17. Chalmer MA, Kogelman LJA, Ullum H, et al. Population-based characterization of menstrual migraine and proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6:e2313235.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Diamond ML, Cady RK, Mao L, et al. Characteristics of migraine attacks and responses to almotriptan treatment: a comparison of menstrually related and nonmenstrually related migraines. Headache 2008;48:248-258.ArticlePubMed

- 19. Silberstein SD, Massiou H, McCarroll KA, Lines CR. Further evaluation of rizatriptan in menstrual migraine: retrospective analysis of long-term data. Headache 2002;42:917-923.ArticlePubMed

- 20. van Casteren DS, Verhagen IE, van der Arend BWH, van Zwet EW, MaassenVanDenBrink A, Terwindt GM. Comparing perimenstrual and nonperimenstrual migraine attacks using an e-diary. Neurology 2021;97:e1661-e1671.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 21. Granella F, Sances G, Allais G, et al. Characteristics of menstrual and nonmenstrual attacks in women with menstrually related migraine referred to headache centres. Cephalalgia 2004;24:707-716.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 22. Pinkerman B, Holroyd K. Menstrual and nonmenstrual migraines differ in women with menstrually-related migraine. Cephalalgia 2010;30:1187-1194.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 23. Vetvik KG, Benth JŠ, MacGregor EA, Lundqvist C, Russell MB. Menstrual versus non-menstrual attacks of migraine without aura in women with and without menstrual migraine. Cephalalgia 2015;35:1261-1268.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 24. MacGregor EA, Victor TW, Hu X, et al. Characteristics of menstrual vs nonmenstrual migraine: a post hoc, within-woman analysis of the usual-care phase of a nonrandomized menstrual migraine clinical trial. Headache 2010;50:528-538.ArticlePubMed

- 25. Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004;24 Suppl 1:9-160.ArticlePubMed

- 26. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018;38:1-211.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 27. Marcus DA, Bernstein CD, Sullivan EA, Rudy TE. A prospective comparison between ICHD-II and probability menstrual migraine diagnostic criteria. Headache 2010;50(4):539-550.ArticlePubMed

- 28. Dowson AJ, Massiou H, Aurora SK. Managing migraine headaches experienced by patients who self-report with menstrually related migraine: a prospective, placebo-controlled study with oral sumatriptan. J Headache Pain 2005;6:81-87.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 29. Somerville BW. The role of estradiol withdrawal in the etiology of menstrual migraine. Neurology 1972;22:355-365.ArticlePubMed

- 30. Somerville BW. Estrogen-withdrawal migraine. II. Attempted prophylaxis by continuous estradiol administration. Neurology 1975;25:245-250.ArticlePubMed

- 31. Somerville BW. Estrogen-withdrawal migraine. I. Duration of exposure required and attempted prophylaxis by premenstrual estrogen administration. Neurology 1975;25:239-244.ArticlePubMed

- 32. MacGregor EA. Oestrogen and attacks of migraine with and without aura. Lancet Neurol 2004;3:354-361.ArticlePubMed

- 33. Smith YR, Stohler CS, Nichols TE, Bueller JA, Koeppe RA, Zubieta JK. Pronociceptive and antinociceptive effects of estradiol through endogenous opioid neurotransmission in women. J Neurosci 2006;26:5777-5785.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 34. Paredes S, Cantillo S, Candido KD, Knezevic NN. An association of serotonin with pain disorders and its modulation by estrogens. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:5729.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 35. Labastida-Ramírez A, Rubio-Beltrán E, Villalón CM, MaassenVanDenBrink A. Gender aspects of CGRP in migraine. Cephalalgia 2019;39:435-444.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 36. Raffaelli B, Storch E, Overeem LH, et al. Sex hormones and calcitonin gene-related peptide in women with migraine: a cross-sectional, matched cohort study. Neurology 2023;100:e1825-e1835.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 37. Colson N, Fernandez F, Griffiths L. Genetics of menstrual migraine: the molecular evidence. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2010;14:389-395.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 38. Li L, Liu R, Dong Z, Wang X, Yu S. Impact of ESR1 gene polymorphisms on migraine susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e0976.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 39. Sutherland HG, Champion M, Plays A, et al. Investigation of polymorphisms in genes involved in estrogen metabolism in menstrual migraine. Gene 2017;607:36-40.ArticlePubMed

- 40. De Marchis ML, Barbanti P, Palmirotta R, et al. Look beyond Catechol-O-Methyltransferase genotype for cathecolamines derangement in migraine: the BioBIM rs4818 and rs4680 polymorphisms study. J Headache Pain 2015;16:520.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 41. Sullivan AK, Atkinson EJ, Cutrer FM. Hormonally modulated migraine is associated with single-nucleotide polymorphisms within genes involved in dopamine metabolism. Open J Genet 2013;3:38-45.ArticlePDF

- 42. An X, Fang J, Lin Q, Lu C, Ma Q, Qu H. New evidence for involvement of ESR1 gene in susceptibility to Chinese migraine. J Neurol 2017;264:81-87.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 43. CoŞkun S, Yůcel Y, Çim A, et al. Contribution of polymorphisms in ESR1, ESR2, FSHR, CYP19A1, SHBG, and NRIP1 genes to migraine susceptibility in Turkish population. J Genet 2016;95:131-140.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 44. Allais G, Bussone G, D’Andrea G, et al. Almotriptan 12.5 mg in menstrually related migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia 2011;31:144-151.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 45. Massiou H, Jamin C, Hinzelin G, Bidaut-Mazel C; French Naramig Collaborative Study Group. Efficacy of oral naratriptan in the treatment of menstrually related migraine. Eur J Neurol 2005;12:774-781.ArticlePubMed

- 46. Martin V, Cady R, Mauskop A, et al. Efficacy of rizatriptan for menstrual migraine in an early intervention model: a prospective subgroup analysis of the rizatriptan TAME (Treat A Migraine Early) studies. Headache 2008;48:226-235.ArticlePubMed

- 47. Nett R, Mannix LK, Mueller L, et al. Rizatriptan efficacy in ICHD-II pure menstrual migraine and menstrually related migraine. Headache 2008;48:1194-1201.ArticlePubMed

- 48. Landy S, Savani N, Shackelford S, Loftus J, Jones M. Efficacy and tolerability of sumatriptan tablets administered during the mild-pain phase of menstrually associated migraine. Int J Clin Pract 2004;58:913-919.ArticlePubMed

- 49. Mannix LK, Martin VT, Cady RK, et al. Combination treatment for menstrual migraine and dysmenorrhea using sumatriptan-naproxen: two randomized controlled trials. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:106-113.ArticlePubMed

- 50. Loder E, Silberstein SD, Abu-Shakra S, Mueller L, Smith T. Efficacy and tolerability of oral zolmitriptan in menstrually associated migraine: a randomized, prospective, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Headache 2004;44:120-130.ArticlePubMed

- 51. Tuchman M, Hee A, Emeribe U, Silberstein S. Efficacy and tolerability of zolmitriptan oral tablet in the acute treatment of menstrual migraine. CNS Drugs 2006;20:1019-1026.ArticlePubMed

- 52. Allais G, Tullo V, Benedetto C, Zava D, Omboni S, Bussone G. Efficacy of frovatriptan in the acute treatment of menstrually related migraine: analysis of a double-blind, randomized, multicenter, Italian, comparative study versus zolmitriptan. Neurol Sci 2011;32 Suppl 1:S99-S104.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 53. Güven B, Güven H, Çomoğlu S. Clinical characteristics of menstrually related and non-menstrual migraine. Acta Neurol Belg 2017;117:671-676.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 54. Bartolini M, Giamberardino MA, Lisotto C, et al. Frovatriptan versus almotriptan for acute treatment of menstrual migraine: analysis of a double-blind, randomized, cross-over, multicenter, Italian, comparative study. J Headache Pain 2012;13:401-406.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 55. Al-Waili NS. Treatment of menstrual migraine with prostaglandin synthesis inhibitor mefenamic acid: double-blind study with placebo. Eur J Med Res 2000;5:176-182.PubMed

- 56. Allais G, Bussone G, Tullo V, et al. Frovatriptan 2.5 mg plus dexketoprofen (25 mg or 37.5 mg) in menstrually related migraine. Subanalysis from a double-blind, randomized trial. Cephalalgia 2015;35:45-50.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 57. Cady RK, Diamond ML, Diamond MP, et al. Sumatriptan-naproxen sodium for menstrual migraine and dysmenorrhea: satisfaction, productivity, and functional disability outcomes. Headache 2011;51:664-673.ArticlePubMed

- 58. Vetvik KG, MacGregor EA. Menstrual migraine: a distinct disorder needing greater recognition. Lancet Neurol 2021;20:304-315.ArticlePubMed

- 59. MacGregor EA, Komori M, Krege JH, et al. Efficacy of lasmiditan for the acute treatment of perimenstrual migraine. Cephalalgia 2022;42:1467-1475.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 60. Vetvik KG, MacGregor EA, Lundqvist C, Russell MB. Contraceptive-induced amenorrhoea leads to reduced migraine frequency in women with menstrual migraine without aura. J Headache Pain 2014;15:30.ArticlePDF

- 61. Verhagen IE, de Vries Lentsch S, van der Arend BWH, le Cessie S, MaassenVanDenBrink A, Terwindt GM. Both perimenstrual and nonperimenstrual migraine days respond to anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (receptor) antibodies. Eur J Neurol 2023;30:2117-2121.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 62. Brandes JL, Poole AC, Kallela M, et al. Short-term frovatriptan for the prevention of difficult-to-treat menstrual migraine attacks. Cephalalgia 2009;29:1133-1148.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 63. Silberstein SD, Elkind AH, Schreiber C, Keywood C. A randomized trial of frovatriptan for the intermittent prevention of menstrual migraine. Neurology 2004;63:261-269.ArticlePubMed

- 64. Hu Y, Guan X, Fan L, Jin L. Triptans in prevention of menstrual migraine: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Headache Pain 2013;14:7.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 65. Sances G, Martignoni E, Fioroni L, Blandini F, Facchinetti F, Nappi G. Naproxen sodium in menstrual migraine prophylaxis: a double-blind placebo controlled study. Headache 1990;30:705-709.ArticlePubMed

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- Sex hormones and diseases of the nervous system

Hyman M. Schipper

Brain Medicine.2025; : 1. CrossRef - Evidence-Based Recommendations on Pharmacologic Treatment for Migraine Prevention: A Clinical Practice Guideline from the Korean Headache Society

Byung-Su Kim, Pil-Wook Chung, Jae Myun Chung, Kwang-Yeol Park, Heui-Soo Moon, Hong-Kyun Park, Dae-Woong Bae, Jong-Geun Seo, Jong-Hee Sohn, Tae-Jin Song, Seung-Han Lee, Kyungmi Oh, Mi Ji Lee, Myoung-Jin Cha, Yun-Ju Choi, Miyoung Choi

Headache and Pain Research.2025; 26(1): 5. CrossRef - Morning Headaches: An In-depth Review of Causes, Associated Disorders, and Management Strategies

Yooha Hong, Mi-Kyoung Kang, Min Seung Kim, Heejung Mo, Rebecca C. Cox, Hee-Jin Im

Headache and Pain Research.2025; 26(1): 66. CrossRef - Migraine in Women: Inescapable Femaleness?

Soo-Kyoung Kim

Headache and Pain Research.2024; 25(1): 1. CrossRef - Three-month treatment outcome of medication-overuse headache according to classes of overused medications, use of acute medications, and preventive treatments

Sun-Young Oh, Jin-Ju Kang, Hong-Kyun Park, Soo-Jin Cho, Yooha Hong, Mi-Kyoung Kang, Heui-Soo Moon, Mi Ji Lee, Tae-Jin Song, Young Ju Suh, Min Kyung Chu

Scientific Reports.2024;[Epub] CrossRef - Understanding the Connection between the Glymphatic System and Migraine: A Systematic Review

Myoung-Jin Cha, Kyung Wook Kang, Jung-won Shin, Hosung Kim, Jiyoung Kim

Headache and Pain Research.2024; 25(2): 86. CrossRef

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link-

Cite this Article

Cite this Article

- Cite this Article

-

- Close

- Download Citation

- Close

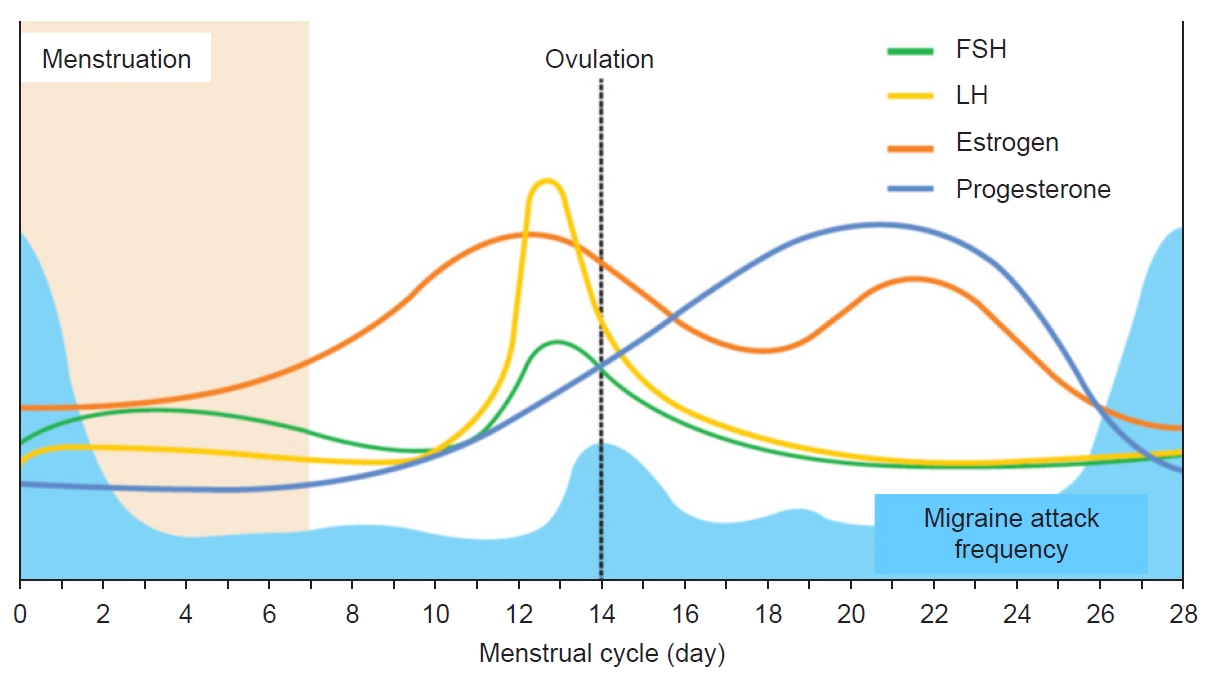

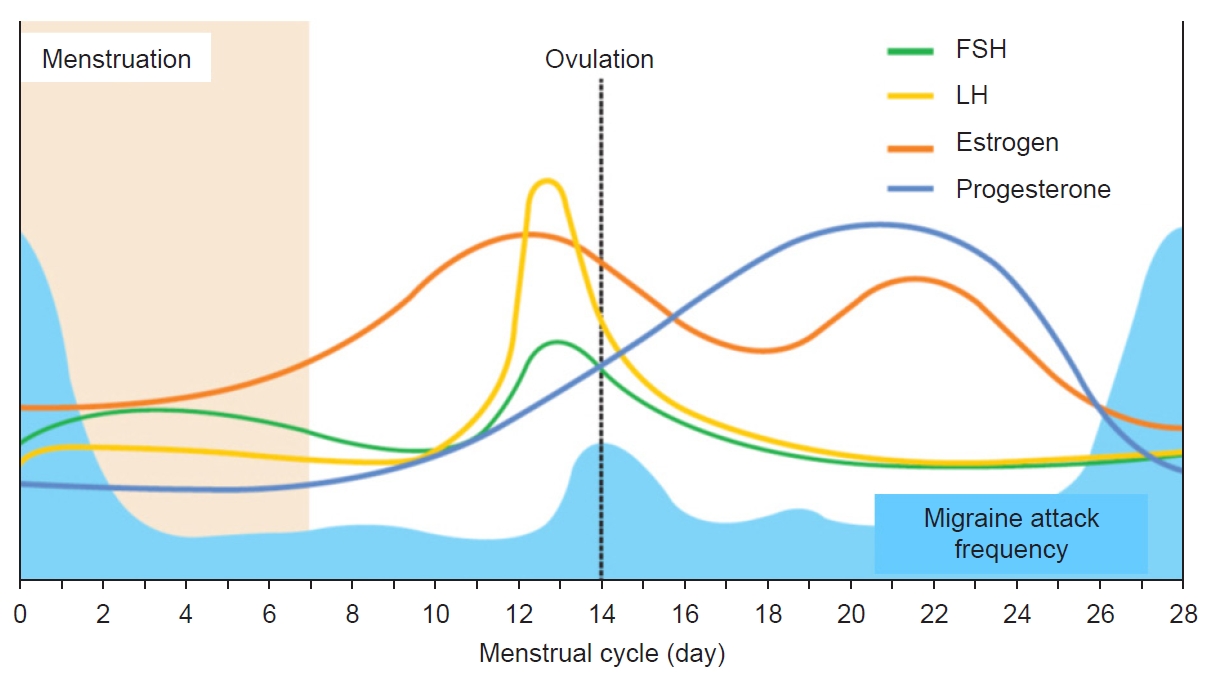

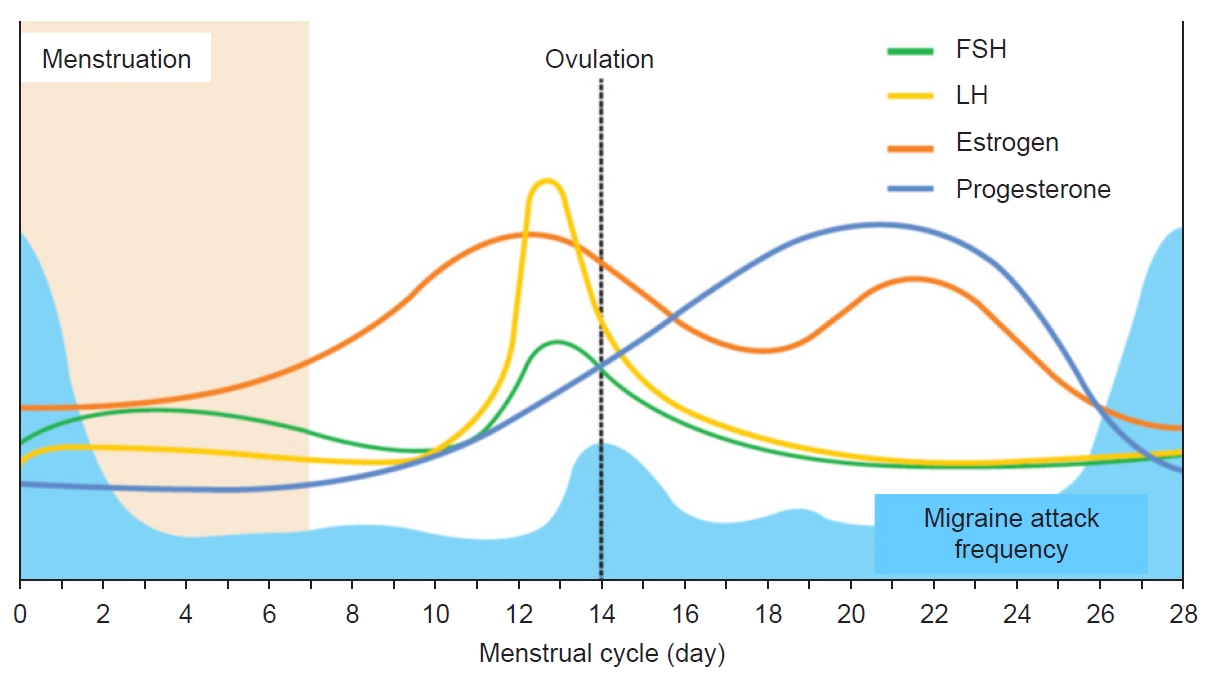

- Figure

Figure 1.

| Pure menstrual migraine |

| A. Attacks, in a menstruating woman*, fulfilling criteria for migraine without/with aura and criterion B below. |

| B. Occurring exclusively on day 1±2 (i.e., days −2 to +3)† of menstruation in at least two out of three menstrual cycles and at no other times of the cycle. |

| Menstrually-related migraine |

| A. Attacks, in a menstruating woman*, fulfilling criteria for migraine without/with aura and criterion B below. |

| B. Occurring on day 1±2 (i.e., days −2 to +3)† of menstruation in at least two out of three menstrual cycles, and additionally at other times of the cycle. |

| Acute treatment | Short-term prevention |

|---|---|

| NSAIDs49 | NSAIDs65 |

| Ergotamine derivatives21 | |

| Triptans | Triptans |

| Frovatriptan52 | Frovatriptan63 |

| Naratriptan45 | Naratriptan22,23 |

| Sumatriptan48 | Sumatriptan24 |

| Zolmitriptan50 | Zolmitriptan64 |

| Almotriptan44 | |

| Rizatriptan46 |

*For the purposes of ICHD-3, menstruation is considered to be endometrial bleeding resulting either from the normal menstrual cycle or from the withdrawal of exogenous progestogens, as in the use of combined oral contraceptives or cyclical hormone replacement therapy. †The first day of menstruation is day 1 and the preceding day is day −1; there is no day 0.

NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

Table 1.

Table 2.

TOP

KHS

KHS